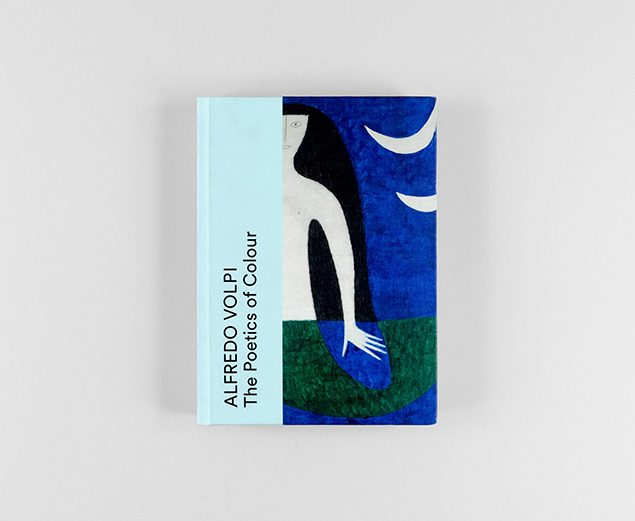

Alfredo Volpi, La poétique de la couleur

Alfredo Volpi

Sans titre, début des années 1960

Tempera sur toile

105×70 cm

Collection Privée, São Paulo

The NMNM presents the very first retrospective in a public institution outside Brazil of Alfredo Volpi: a major Brazilian artist born in Lucca (Italy) in 1896 and who moved to São Paulo’s Cambuci Italian neighborhood in 1898. Alfredo Volpi died in 1988 in São Paulo.

The aim of the exhibition is to retrace Volpi’s career, starting from his early oil paintings in the ’40s – mostly landscapes and ‘cityscapes’ – to the works of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, in which the same subjects are metamorphosed into colorful geometric compositions, oneiric archetypes of the façades of buildings and festive banners, and a humble and poetic ‘algorithm’ that gives Volpi the chance to make infinite color variations on the same subject.

The exhibition features more than 70 works retracing the history of this independent and self-taught painter, whose fascination for the Italian early Renaissance, for Matisse, Morandi and the sphere of popular culture led him to win the Best National Prize at the 2nd São Paolo Biennale with ‘Di Cavalcanti’, and intrigued the celebrated English critic Herbert Read, who described him as an artist “… aware of the general movement, but who created something contemporary with an indigenous theme: the shapes and colors of Brazilian modern architecture.”

Volpi is probably the most-loved Brazilian artist of the 20th century, but has remained little known outside of Latin America until now. Having trained at an early age as a woodcarver and bookbinder, he began working as a commercial artist, assisting a wall painter and decorating the houses of the rich bourgeoisie of São Paulo. This ‘school’, as Mario Pedrosa wrote, allowed him “to learn the finest techniques” and to earn enough money to develop his artistic skills and desires, avoiding academism and developing his own imaginary.

By the end of the ’40s, cityscapes and seascapes that he had started depicting in the 1910s had turned into depictions of building façades and rows of festive banners, dissolving into complete abstraction in the wake of his close observation of the humble industrial area around him. Experience and observation are the most important aspects of the creative process: a direct experience transposed through the sole use of memory of the pictorial space.

When Volpi first achieved success in the early ’30s, he was indifferent to academic styles and precepts, and he was detached from the vanguards of his time. The friendship with celebrated artists like Emygdio de Souza and Ernesto de Fiori had surely influenced him to welcome certain aspects of the modernist style, as well as his participation in the Santa Helena artists’ group, but his direct experience of the works of other great European artists exhibited in Brazil throughout the ’40s became a new source of inspiration for his formal solutions and space organization.

During the ’40s, from Paul Cezanne to Henri Matisse, from Mario Sironi and Carlo Carrà to Giorgio Morandi, Alfredo Volpi would learn how to remodel the pictorial space, and as Lorenzo Mammi wrote, “those new poetic coordinates oblige Volpi to modify his media. The transition from oil to tempera allows the movement of the brushstroke to be now a visible and constitutive element of his paintings, granting at the same time the absolute value of the color independently from the light and texture; in other words, it allows conciliating Morandi with Matisse.”

Volpi does not follow a conceptual program. “Volpi paints Volpi” as Willys de Castro wrote, perceiving the potential of the modernity of popular art and creating a unique synthesis between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, and between fine and naïve art. Popular art allowed him to find an atemporal and universal shape, far from European transcendent rationality and North American empirics.

In 1950, thanks to Osir Art, a ceramic laboratory where he worked with major Brazilian artists, like Candido Portinari, Mario Zannini and Paolo Rossi Osir, he was finally able to travel to Italy and discover the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, painted by Giotto da Bondone. Volpi was deeply struck, and studied its frescos for many days, fascinated by the fresco technique, the use of ultramarine blue and the humanization of the saints and figures represented. During the same journey, he had the chance to visit Arezzo, and after having observed the famous frescos of the ‘Legend of the True Cross’ painted by Piero della Francesca, he surprisingly decided that early Renaissance was far more interesting for the spatial research he was already carrying out. Enchanted by Margheritone d’Arezzo and Cimabue, two of the major artists of the 14th century, Volpi studied the rigid composition of their ‘Madonna and Child’; he liked what he called the ‘ovo frito’ (fried egg) spatial organization, an initial two-dimensional background onto which the Madonna and Child are inscribed. Volpi was not interested in the perspective or the search for realness of Piero della Francesca – he had already abandoned it in his own work – but instead was interested in some spatial solutions found in Paolo Uccello’s banners, used in his frescos to create new and fluctuating spaces.

Despite the great success that he attained over last three decades of his life, the story of Volpi is one of a simple, reserved man devoted entirely to his work, and one who never forgot his humble origins. A man who every day, until the age of 88, would build his own frames and stretch the linen over them for his paintings, meticulously preparing the pigments and earths to create the magic of color. What today seems incredible is that so few people in Europe and the US know anything about his life and achievements: his works have never been exhibited institutionally as solo shows in Europe, except for his presence as an invited artist at the Venice Biennale of 1952 and 1964 or a handful of commercial exhibitions.

Volpi the ‘colorist’, like Morandi for the Italians, became a real hero and a legend in Brazil, and today we can easily find his role in the international vanguard movement as an isolated figure, midway between the modernist, concrete and neo-concrete movements in Brazil, a bit like Morandi caught between the experiences of the Novecento and the Metaphysical movements in Italy. Volpi’s unique and universal language must be considered a collective cultural and visual heritage and a positive example in the history of immigration.

A catalogue co-published by Capivara Editora and Mousse Publishing gathering texts from Lorenzo Mammi, Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, Cristiano Raimondi will be released around the end of April in French and English

Curator: Cristiano Raimondi

With the support of Instituto Alfredo Volpi de Arte Moderna, São Paulo